Saturdays are for Day Trips to The Portland Museum of Art

Going to school in Cambridge, MA means I'm extremely close to Portland, ME - a quaint area known for a burgeoning art scene and the ease of weekend trip-ability. This past Saturday, courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums Student Board & Student Guide program, my friends and I took a bus to check out all the fuss for ourselves.

Given that the semester is coming to a close and that senior spring nostalgia is hitting (despite the fact that I'm a junior and fully have another school year ahead of me), escaping campus provided unexpected relief from some self-imposed woes. It took exploring the Portland Museum of Art to make me feel at home, in a city I had never visited before. And to catalyze that comfort, I have Joan Miró to thank.

After scoping out the Biennial Show in which I found photographs by John Harlow who spliced his imagery with his wife's journal entries, Anne Buckwater's innovative mounting method for her paper works, and Becca Albee's intriguing commentary on feminist literature by condensing her annotations per chapter on one page, I peeled away from my peers and travelled upstairs.

John Harlow, Garish Sunlight, 2016

Anne Buckwalter, The Republic of Hysteria, 2017

Becca Albee, RADICAL FEMINIST THERAPY: Working in the Context of Violence, 2016

Seeking fresh air and a moment of silence, I found myself face to face with a time machine. No, not actually. But I stumbled upon a Miró I had never seen before. But the gestural and jovial marks familiar to this artist transported me to my grandmother's apartment circa 2003. I'm sitting in her kitchenette eating turkey and butter sandwiches on challah rolls, and laughing at something my sister said that my grandmother must not have found as amusing. While I'm no longer 6 years old nor in my grandmother's Miami Beach apartment, standing in front of this Miró provided me a momentary glimpse into my past.

Joan Miró, Untitled, circa 1981

This is what I love about art: it's ability to transport and to resonate. Art has a way of making you feel something, and allowing you to see in abstraction what you're looking for. And what I was looking for, in that moment, was comfort. And comfort I found in this untitled "chickadee" looking work.

(left) Joan Miró, The First Spark of Day III, 1966

(right) Adolph Gottlieb, Green Ground, 1968

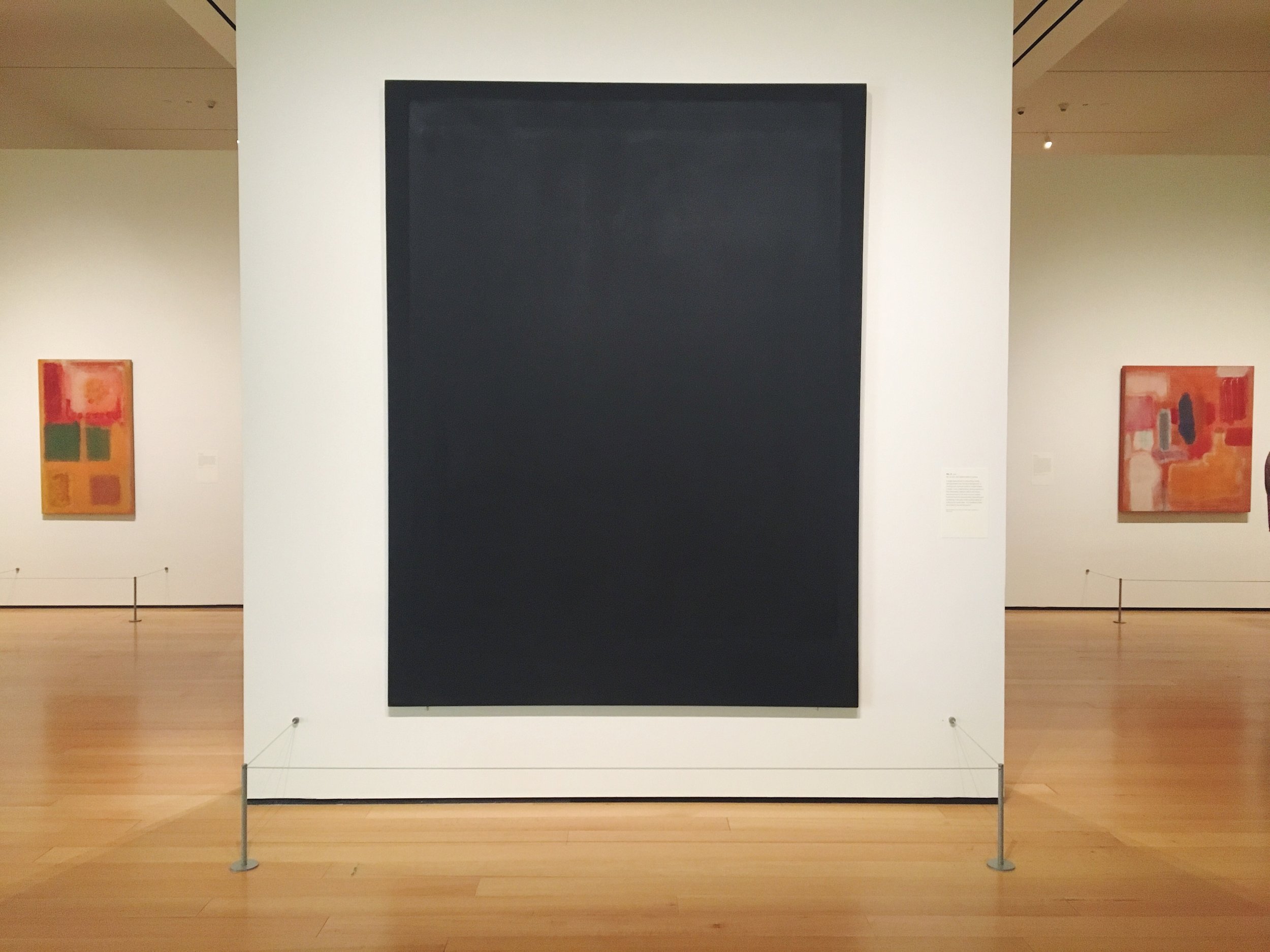

In another room on a different floor, I encountered a corner that instantly made me smile. Perhaps it was the brighter colors to contrast my somber mood, but I also found it shocking that the painting that most moved me was another Miró. This one, entitled The First Spark of Day III simply made me happy. And having it juxtaposed with Adolph Gottlieb's Green Ground created an instant happy place (or corner, at that) for me in the museum.

Other works in the museum were less heart striking, but I still enjoyed encountering new artists and new mediums. Like this Porch Mattress by Duncan Hewitt - it's made entirely of painted wood! Or this René Magritte painting that had me doing a double take at first, before I noticed the slight of hand ;)

Duncan Hewitt, Porch Mattress, 2000

René Magritte, The Tempest, circa 1944

So I'd say that the two hour bus ride to Portland was well worth it, given that it brought me instantly closer to home - and that trip is usually a 3 hour flight.

The Harvard Art Museums Student Board & Student Guide Program, 2018. Courtesy of @harvardarthappens.

Xx, Maia